|

Aerial photo of forest canopy in Monteverde,

Costa Rica. The trees with golden-yellow

crowns are Ocotea monteverdensis. Click

here for more pictures of this tree.

|

For the past five years or so I have been captivated by a tree with a long name, Ocotea monteverdensis. In fact, some of my friends say I’m obsessed. Why, you may ask, this one particular tree species? Is it because it grows to a huge size – five feet in diameter, 115 feet tall – and is stunningly beautiful when flowering, or even when not in flower?

Perhaps it's because it's endemic to (only found in) the Monteverde area of Costa Rica. Or because it's an important source of fruit for a number of large, unique, and threatened birds.

Or maybe because I discovered that there are less than 1,000 mature trees left on the planet, so that the IUCN has red-listed it as critically endangered. Or maybe because we have learned that when the Three-wattled Bellbird passes through Monteverde in June, July, and August, every third year this tree provides the bellbirds with their favorite fruit. Perhaps it's because it's currently growing almost exclusively in patches of remaining old growth forest, nearly none of which are protected. And, as I'll get to later, its relationship with the bellbird gives some reason to hope that despite its critically endangered status, Ocotea monteverdensis may be around for a while longer.

For all of the reasons above, how could this tree NOT be captivating?

|

From left to right: Resplendent Quetzal, Three-wattled Bellbird, Black Guan, Oilbird. All feed on Ocotea monteverdensis.

|

|

O. m. fruit. Note the red cupule

on the right.

|

Ocotea monteverdensis (hereafter called O. m.) is a member of the plant family Lauraceae, also known as the laurel or avocado family. Like the avocado we eat, fruits from this family have a single seed and a soft, fleshy rind that many birds and mammals like to eat. The fruit of O. m. is on average 1.85 cm in length and among the largest of the locally known “aguacatillos” or “small avocados.” It is known to be eaten by about ten bird species, all of whom have large enough gapes to get the whole fruits (with seeds) into their mouths. Like many aguacatillos, O. m. fruit are held in red cupules to make them more noticeable to birds. O. m. leaves are fairly long and narrow, a shiny dark green, and have prominent leaf veins. Newly growing stems are a rusty red color and are quite hairy.

|

Newly growing O. m. stem with rusty red hairs.

|

We know from specimens collected by botanists since the 1970’s that O. m. is found almost entirely on the Pacific side of the Tilaran Mountains of Costa Rica between 1200 and 1500 m elevation, in a 2-km-wide 12-km-long band centered around Monteverde. This restricted range corresponds to the moist portion of the premontane wet forest life zone and likely reflects specific climatic requirements. Much of the primary forest that once covered this small natural range of O. m. has been cut down to create pastures, coffee plantations, roads, and towns. Mature O. m. trees that are capable of producing fruit are now only found in fragments of that remaining forest.

|

Aerial photo of fragmented landscape.

|

Back in 2015, I realized that June-July was going to be a major flowering period for O. m. (which on average, only flowers every three years). And it dawned on me that the best way to locate most of the remaining trees would be to take aerial photographs across the entire range of the species. When flowering, O. m.’s yellow flowers usually cover the entire crown and contrast nicely with surrounding green leaves of neighboring trees. Giancarlo Pucci (founder of the Magical Trees Foundation) is a Costa Rican photographer who loves trees, loves to do aerial photography, and cares about conservation. He agreed to join the pilot of a small plane to fly over Monteverde and the surrounding region and photograph the O. m. trees in flower. But throughout June and early July there was too much cloud cover and/or too much wind for a flight. Finally, on July 7, the clouds lifted and Giancarlo was able to spend several hours taking 130 spectacular high-resolution photographs.

Each individual O. m. tree shows up because of its thousands of very small, golden yellow flowers. Using these photos, I worked with Randy Chinchilla of the Monteverde Institute to count the number of mature O. m. trees that flowered that year, and to make a map of every tree we could identify from the aerial photos.

|

Aerial photo with individual O. m. trees visible.

|

During the mapping process, we were able to estimate the number of mature O. m. trees remaining on the planet. We counted approximately 600 trees in the photos. Considering areas not covered by the aerial photos and the results of “ground-truthing” I estimate that 770 mature O. m. trees remain.

When O. m. is fruiting during June to August, it's eaten by a number of large and unique birds, several of which are also threatened and found only in wet highland forests. Of particular interest is the Three-wattled Bellbird which is endemic to Central America and ranges between southeastern Honduras and western Panama. One of the two largest remaining populations resides in the Tilaran mountains in the general vicinity of Monteverde from March through August each year (interestingly, this population, and the one in southern Costa Rica and northern Panama, have different sounding calls, or "bonks").

Debra Hamilton and Victorino Molina (with assistance from guides, interns, and ornithological associations) have been conducting censuses of bellbirds as they pass through “the Monteverde zone” for about two decades. They have noted that the birds concentrate in different areas of “the zone” in different years. Assuming that these concentration patterns are determined by what fruit the birds are eating, back in 2005 Debra, Rhine Singleton, and I started a six year study of the principal fruiting tree species in these areas between 1200 and 1500 m. Our study demonstrated that the preferred fruit of the bellbird is that of our friend O. m. Whenever and wherever O. m. is fruiting, bellbirds can be found nearby. And, our data show that O. m. generally only bears abundant fruit every three years; during these years, a distinct pattern of concentration of birds around areas with O. m. trees can be seen. In other years, other species of fruit trees attract bellbirds and consequently, they concentrate in other areas (Hamilton et al., 2018).

Of course, the relationship between fruit-bearing trees and fruit-eating birds is mutually beneficial. The latter get free food and the former get their seeds spread across the landscape. However, the quality of this “spreading of seeds” is not always the same. The bellbird and O. m. appear to have a special relationship in this regard.

The nature of this relationship was illustrated by Dan Wenny and Doug Levy when they studied Ocotea endresiana, a species very closely related to O. m. Wenny and Levy studied where various species of fruit-eating birds distributed the seeds. Toucans, guans, quetzals, mountain robins and others all dropped seeds fairly close to the adult fruiting tree they were feeding on (within 20 m). Bellbirds, by contrast, habitually went to their “perching branch” to finish digesting their fruit - consequently, they regurgitated their seeds near their perch (this behavior can be seen at 30 seconds here). Perches typically are on mid-canopy, dead branches in slightly open gaps in the forest canopy. These locations just happen to be ideal for germination and growth of both Ocotea endresiana and O. m. Directly under parent trees, soil microbes pathogenic to the tree species (including seedlings) often concentrate. But bellbird perches typically are located further from parent trees (>50 m). And, perhaps more importantly, the canopy cover is frequently closed under the parent tree, but more open under the bellbird perch “mini-gap.” This means that newly germinating seedlings (and later when they are growing as saplings) receive more light for growth and survival. Wenny and Levy's study revealed that seedlings were twice as likely to survive where bellbirds dropped seeds as where other birds did. They were also one-third less likely to be infected with pathogenic root fungi.

|

Young O. m. sapling growing in a "mini-gap."

|

So one can see how O. m. trees and the bellbird may have co-evolved to be particularly beneficial to each other. O. m., it would seem, has evolved to produce fruit that is nutritious, easily located, and the right size for the bellbird to swallow whole and digest slowly. And the bellbird, perhaps, has evolved behaviors that result in the distribution of O. m. seeds in ideal locations. Walking through the forests here, I sometimes find small clusters of O. m. saplings that are some distance (> 60 m) from any parent tree. These trees usually appear to be the same age. It is easy enough to imagine that years before - above these clusters - bellbirds sat on their perches regurgitating seeds. And, if we have the imagination to protect enough habitat for the bellbirds, they will continue to spread seeds and help a tree species that not only provides food for a variety of exotic tropical birds, but, is really quite captivating.

|

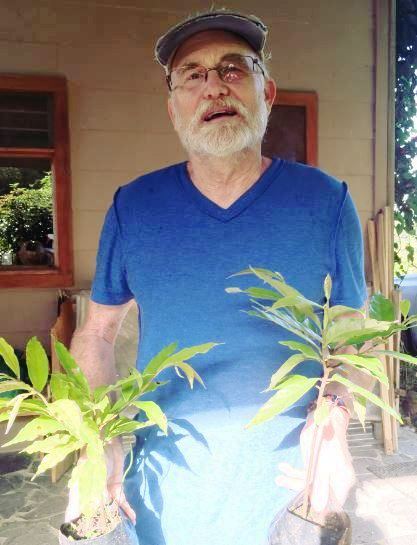

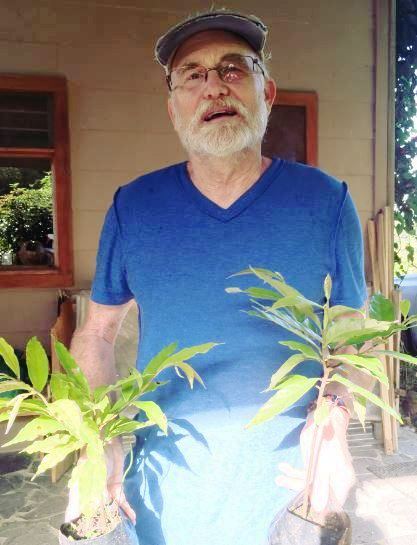

Dev with two Ocotea

monteverdensis seedlings.

|

Dev Joslin is a scientist who enjoys research that combines his interests and expertise in forest ecology, soils, ornithology, and reforestation. With a masters and a Ph. D. in forestry and soil science, he conducted research for 30 years in North America and Europe on air pollution and climate change impacts on forests, soils, and streams. He has been an active birder and conservationist in Tennessee and Costa Rica for the past 25 years. He and his wife, Harriet, have lived in Monteverde for the past 13 years, during which time he has been active in community organizations, “gentleman farming,” and conservation research involving frugivorous birds and their relationships to wild avocados.

REFERENCES

Wenny, D.G. and Levey, D.J. 1998. Directed seed dispersal by bellbirds in a tropical cloud forest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A 95(11): 6204-6207.